Congrats! You’ve built a binary classifier that you’re convinced is totally awesome.

But how do you quantify just how awesome this model is? And more specifically, how do you communicate this model’s level of awesomeness to your manager/product owner/stakeholder/random-person-on-the-street?

This is where performance metrics such as precision and recall come into play, and we’ll attempt to explain the intuition around these in addition to their definitions.

What is the positive class?

If you’ve built a binary classifier, perhaps the first step in determining your performance metric is to select a “positive” class. This is easy in some instances (ex. coronavirus test result) and less so in others (ex. determining if your pet is either a cat or a chinchilla). But establishing these definitions early (and stating them explicitly) will save a lot of confusion down the road.

False negatives vs. true positives

Something I struggled with initially was what exactly did we mean by a “false negative”? Was it a true negative that we classified incorrectly? Or did the model return an incorrect (and therefore false) prediction of negative? In other words, from whose perspective do we consider this classification false?

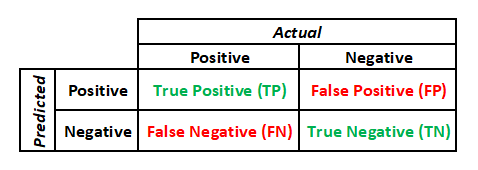

The answer is the latter definition above. The table below sums this up.

Confusion matrix

Once you’ve established your false positives and false negatives, you can display them in a confusion matrix that looks very similar to the table above.

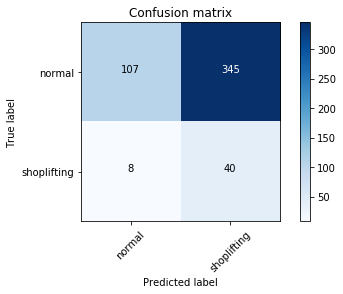

Here is an example for a classifier that attempts to determine if shoplifting is taking place (where we define a shoplifting incident as a positive). Let’s say for example, this model takes video footage from a store surveillance system and looks for certain features (ex. a customer picking up an item and hiding it under his/her shirt) that would indicate shoplifting.

The confusion matrix shows the number of observations for each class and the corresponding predictions from the model.

From the matrix above, we can see that our classifier is rather paranoid and often mistakes normal behavior for shoplifting.

Accuracy

Now we can start to sum up the classifier’s performance using a single value, such as the accuracy, which represents the fraction of correct predictions out of the total. In the shoplifting example, the accuracy is shown by the following:

![]()

Wowza, this is a terrible model.

WARNING: Note that accuracy is a misleading metric in this case due to unbalanced class sizes.

In other words, because we have so few true shoplifting incidences compared to cases of normal behavior, we can easily achieve an accuracy of 0.904 by returning a prediction of “normal” every time. But no one would consider such a classifier to be truly “accurate”.

Precision and Recall

I mentioned earlier that our classifier tends to overpredict shoplifting–how can we incorporate this tendency into a performance metric?

This is where precision and recall come into play. These metrics are class-specific, which means that we must specify a value for both precision and recall for each class returned by the model.

Precision

Precision is the answer to the question: out of the total predictions for a certain class returned by the model, how many were actually correct? For example, the precision for the shoplifting class is:

![]()

![]()

Similarly, for the normal behavior:

![]()

In other words, the model’s predictions for normal behavior were correct 93% of the time, while its predictions for shoplifting were correct only 10% of the time. Yikes.

Recall

I like to think of recall as a class-specific accuracy. How many of the model’s predictions for a certain class were actually correct?

![]()

![]()

![]()

The model correctly identified 83% of the actual shoplifting incidents.

And here we see the trade-off often inherent in precision and recall. The model correctly predicted a good majority (83%) of the actual shoplifting incidents, but at the expense of also erroneously predicting many truly normal behaviors as shoplifting too (nearly 90% of the predicted shoplifting incidents).

This ties into Type I and Type II errors, where a type I error is a false positive (normal behavior incorrectly classified as shoplifting) and a type II error is a false negative (shoplifting incorrectly classified as normal behavior).

For our situation, this boils down to asking if you would rather have the police called on an innocent customer (type I) or lose merchandise to unchecked shoplifters (type II)?

Understanding the costs of type I and type II errors helps to weigh whether you’d like to improve either recall or precision. Often, it’s difficult to do both simultaneously.

F1-Score

However, if you’d like to tie up both precision and recall into one single metric to hand over to your manager/product owner/stakeholder, then the F1-score (sometimes called F-measure) is for you!

This is simply the harmonic mean of the precision and recall for a given class, shown below.

![]()

An F1-score of 1 indicates perfect precision and recall.

If you’d like to place more importance on recall over precision, you can introduce a ![]() term (set

term (set ![]() to a value less than 1 to place more emphasis of precision instead of recall).

to a value less than 1 to place more emphasis of precision instead of recall).

![]()