It’d be an understatement to say that so far, 2020 has been a tough year for nearly everyone. From a global pandemic sickening millions of people to civil unrest rocking the United States and beyond, the world seems to have turned upside down.

If you’ve found yourself in a management position during this chaos, you may be wondering how best to navigate the shift of your company to remote work, the mental health of your team, and the need to address systemic racism in your organization.

Applying the concepts behind “Radical Candor” can help you tackle these issues head-on. And anyone—from CEO’s to individual team members—can start using these lessons today to begin effecting change.

What is Radical Candor?

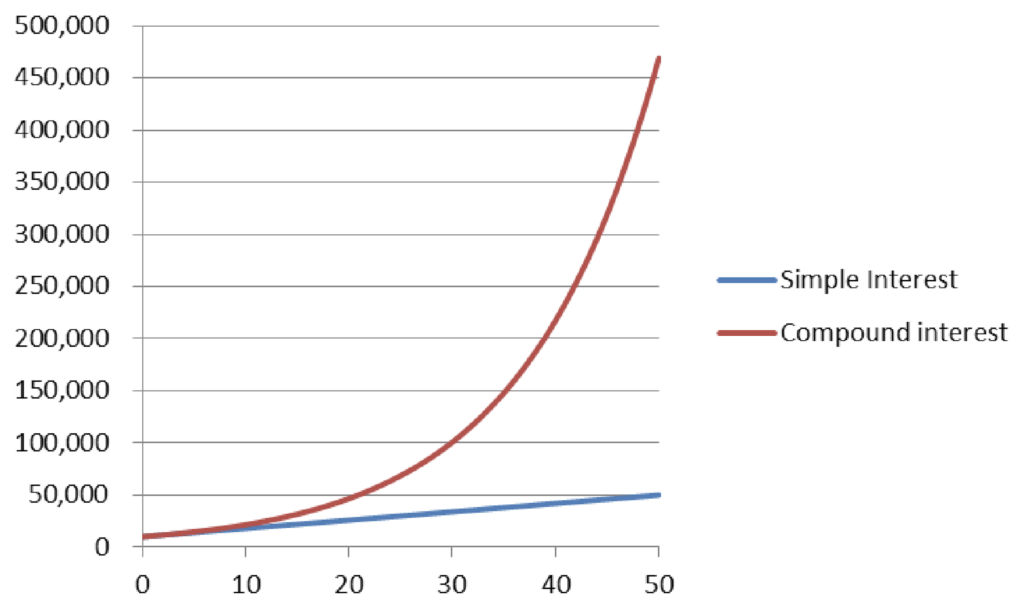

Radical Candor is a 2017 book and management philosophy from Kim Scott, a former manager at Apple and Google. We can sum it up with the following:

Managers should care personally and challenge directly.

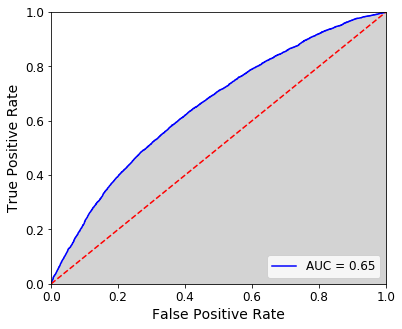

Fleshing this out a bit more, Scott created a matrix to show how managers might fall short on either of these goals.

- Obnoxious Aggression: A manager who isn’t afraid to challenge his/her employees but has made no effort to show that he/she cares about them as people or is invested in their success.

- Ruinous Empathy: A manager who shies away from providing “uncomfortable” criticism out of fear he/she may hurt their employee’s feelings. The vast majority of managers fall into this category, and this is definitely where I naturally land.

- Manipulative Insincerity: A manager who doesn’t bother to give any direct feedback or show interest in his/her employees’ careers. In other words, the worst kind of manager you could get.

- Radical Candor: A manager who recognizes that giving direct feedback in a respectful manner is the best way to help his/her employees succeed and who takes the time to demonstrate personal and professional investment in them.

To sum up, promoting a trusting environment where team members aren’t afraid to challenge each other or their manager is the quickest way to organizational success. I can’t imagine how much time and productivity we lose by withholding from someone the feedback they desperately need if they want to improve their performance at work (or anywhere!).

Compound Interest of Continuous Feedback

Scott also emphasizes the importance of real-time feedback. You might typically bottle up all your feedback for Employee Eric throughout the week and then unleash it on him during your regularly scheduled one-on-one. This can backfire for two reasons.

- Sense of Whiplash: The situation for which you’re giving Eric this feedback—maybe he presented a sloppy demo to marketing on Monday and couldn’t answer any follow-up questions from the team—is now far in the past. Eric might have thought he knocked that presentation out of the park, and he internalized that view for several days before you dashed cold water all over it.

- Repeat Offender: Even worse, Eric might have already given another presentation in the meantime with the same poor quality and lackluster results.

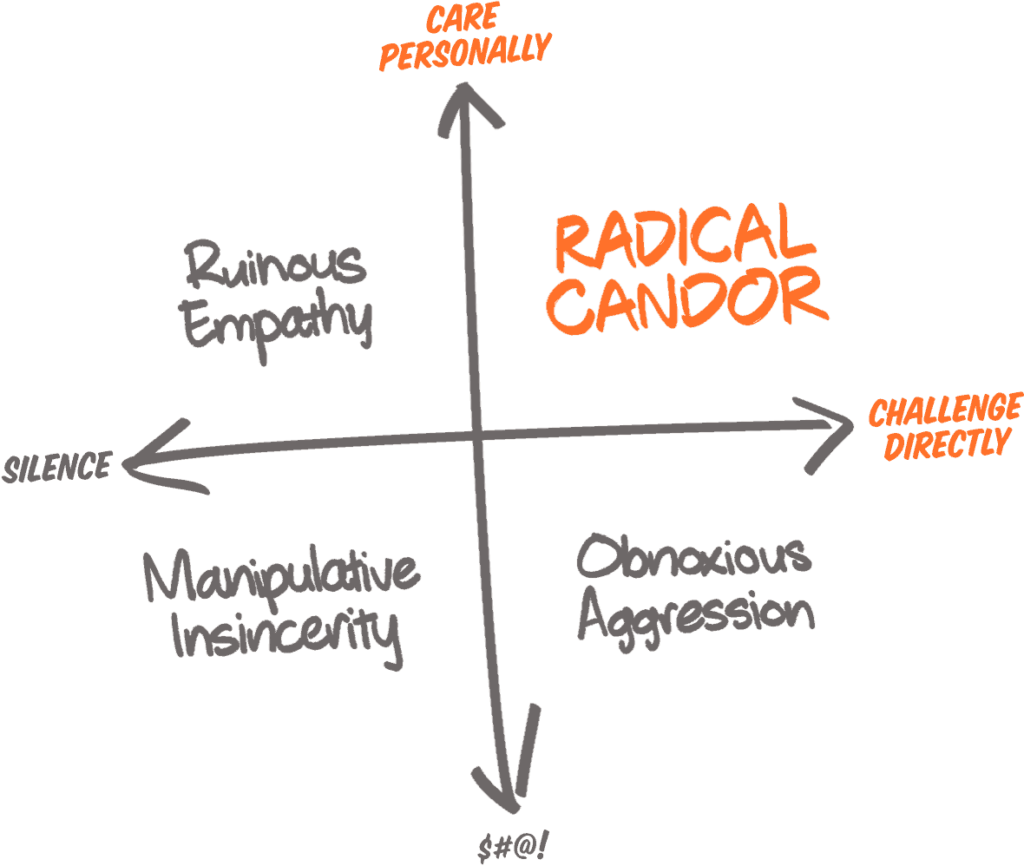

While these two possibilities should be reason enough to instate give feedback immediately whenever possible, I like to think about real-time feedback as analogous to compound interest. Any armchair investor knows that continuously compounded interest grows at a much faster rate than annual or “simple” interest.

Feedback works the same way. If we frequently give small amounts of both positive and negative feedback, the recipient will compound their growth accordingly.

Radical Candor Today

Ok, this all sounds like a great way to run a company in normal times. But these are not normal times. What lessons can we learn for today?

Caring Personally

In typical circumstances, showing that you care personally about your employees or team members might not be that simple. Some people don’t like to discuss their personal lives at work or make small talk, especially introverts. And building trust organically takes time.

But today, checking in on the personal lives of your co-workers and especially your direct reports isn’t just sanctioned—it’s expected.

When we first moved to WFH, we needed to understand how this sudden shift was affecting those around us in the new virtual workplace.

- Are they feeling isolated/burnt-out/unmotivated?

- Do they have kids home from school which affect what hours they can be online?

- Are they caring for elderly relatives or neighbors that might add to whatever stress they’re already feeling?

These conversations started to crack open the door to discuss feelings and invite vulnerability as the line between personal and professional started to blur.

The riots incited by the death of George Floyd and his death itself also warranted checking in with our colleagues.

- How are they coping with the sense of unrest roiling our country?

- How are they feeling in general given current events?

- Has their neighborhood been looted or burned?

- Are they safe?

These last questions, especially, are not ones I ever expected to ask in my role as a manager. And while I hope these circumstances will never be repeated, I am grateful that this situation has destigmatized discussing our personal emotions at work and has given me the opportunity to show that I care personally about my team as human beings.

Confronting Racism

Our current crisis also necessitates that we act along the other axis above—challenging directly.

I admit that I fell into the contingent of white people who put our heads in the sand by believing that by simply being “not racist”, we had overcome ingrained biases and systemic prejudice in this country.

The death of George Floyd and the protests sweeping the country were a long overdue wake-up call, and like many of my peers, I took the time to try and educate myself. I’ve been reading “How to Be an Anti-Racist” by Ibram X. Kendi, which has been eye-opening. I’m ashamed that I wasn’t aware of much of the historical context around concepts of race and hadn’t realized how claiming to be “colorblind” actually hurt communities of color by turning a blind eye to racist policies.

Kendi’s proposed antidote is that we become actively anti-racist. We must constantly evaluate our beliefs, actions, and words for unconscious bias. Yes, that sounds exhausting, and it is. But people of color have been exhausted for centuries—from slavery, from blatant discrimination, from the possibility of being shot by the police—so much so that it has taken a toll on their physical and mental health.

And we must adopt this anti-racist attitude in the workplace, as well, by challenging directly. Kim Scott herself provided an example of unconscious racism embedded in the first edition of her book in a recent blog post. The book suggested using a stuffed monkey called “Whoops the Monkey” as a prop in the office to encourage team members to discuss their mistakes. As a white woman, Scott did not realize that being called a monkey is a common denigration targeted at black people, and bringing this symbol into the office, especially as a representation of mistakes, was inappropriate.

Likely she would never have known had not someone spoken up. Only by directly challenging those we see engaging in acts of racism, even unconsciously, can we start to affect real change in mindsets, language, and policies.

Conclusion

Radical Candor offers an actionable framework for managers (or anyone!) to create an open environment where direct feedback is delivered promptly and where empathy establishes a relationship of trust. These aspirations also have immediate applications to the world of 2020—by engaging with our co-workers’ personal needs amidst continuing stress and by directly confronting racial attitudes and policies in the workplace.