Sometimes I wonder when it happened.

At what point did we take a wrong turn in the space-time continuum, away from the path of sanity and reason, to end up here?

The past few years read like a mash-up of tired Hollywood storylines. A deadly pandemic sweeping the globe, wildfires engulfing the American West, hoodlums storming the Capitol, war in Ukraine, elementary school students gunned down in classrooms.

Even the most mentally resilient among us are numb and drained. The world seems like an increasingly unfriendly place, filled with gun-toting crackpots and rabidly partisan politics.

Rutger Bregman argues otherwise in “Humankind: A Hopeful History”. He believes that certain influences—cognitive biases, excessive government, unscrupulous sociologists—have clouded our judgment and caused us to lose sight of the good inherent in humanity.

Could this be true? Or is Bregman a victim of wishful thinking, a Pollyanna living in an alternative reality?

The power of suggestion

A major theme in Bregman’s book is the idea of nocebos. Nocebos are intrinsically innocuous substances that actively cause harm when patients are led to believe that the substance is dangerous. A medical example might be a patient experiencing side effects from a medication when those side effects have been publicized but suffering no complaints when side effects were not previously listed.

Famous instances of nocebos include the 1939 Monster Study when researchers from the University of Iowa turned several orphans into lifelong stutterers after a round of “negative speech therapy” that criticized any speed imperfections.

Bregman considers our natural human tendency toward negativity bias to be acting as a nocebo within society. Our attraction to negative information served humans well in the distant past when we needed to stay on guard against lions and other imminent physical dangers. But the modern era has twisted this cognitive bias into a threat to today’s fast-paced and interconnected society.

Our addiction to negative stories has been amplified by social media and the 24-hour news cycle. Now the world is regularly depicted to us as a dark and dangerous place. In many cases, these stories are grossly exaggerated. Reports of widespread murder and rape after Hurricane Katrina were pure fiction. And the infamous tale of Kitty Genovese, whose dying screams were ignored by indifferent neighbors? Sensationalistic reporters chose not to include the facts that multiple calls were placed to the police during the murder and that a neighbor rushed to Kitty’s aid and held her as she took her last breath.

Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

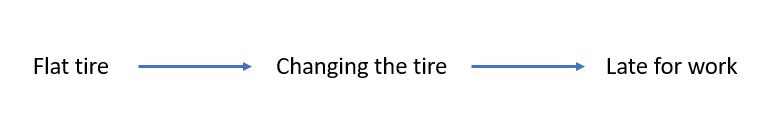

Add the nocebo effect into the mix, and we’ve turned perception into reality. Beliefs lead to actions. And in this case, our belief about the world’s unfolding disasters spawns apathy. Rolf Dobelli in his book “Stop Reading the News: A Manifesto for a Happier, Calmer and Wiser Life” makes the case that all this negative news teaches us “learned helplessness”. We don’t become more engaged citizens through voracious news consumption. Instead, we lose hope that such large intractable problems could ever be solved, and we simply accept our fate.

Belief is destiny

As someone who believes in an objective, physical truth, I found the idea that we can will a world into existence simply mind-blowing. But think of all the myths that people believe—the Catholic Church, the United States of America, the New York Stock Exchange. We’ve collectively agreed that these institutions exist although prior to their inception, there was no physical evidence to suggest that was the case. We willed them into being.

As Yuval Noah Harari detailed in “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind”, the human brain can only juggle about 150 relationships at a time. This phenomenon is called Dunbar’s Number and was first identified when researchers discovered a ratio between a primate’s brain size and the number of individuals in its social group. Applying that ratio to the size of a human brain gives us 150.

This magic number appears time and again throughout human society. Mennonite community sizes, factory employee counts, Christmas card lists—all hover optimally around the 150-person threshold.

If we aren’t able to form meaningful relationships with more than 150 people, how can we build a society across millions of individuals? This is where the concepts of “belief” and “myths” enter the picture. Belief is the glue that holds us together. Simply put, belief scales.

The lack of trust in our society today is so alarming because trust is a form of belief in one another. And without it, the elaborate societal infrastructure we’ve built around us will start to crumble.

Misleading evidence

But should we trust each other? Aren’t humans innately cruel and selfish creatures?

Bregman devoted much of the book to debunking several long-standing pieces of evidence that supposedly showed “humanity’s true face”. Let’s cover a few.

Stanford Prison Experiment

In this famous 1971 experiment run by Dr. Philip Zimbardo, undergraduate students were assigned to act as either prisoners or guards within a newly constructed “jail” in the basement of Stanford University. Over the space of just a few days, the guards meted out increasingly harsh and humiliating punishments to the prisoners. Zimbardo finally plugged the plug on the sixth day due to the rapidly deteriorating conditions. The conclusion from the aborted experiment: we quickly lose our humanity when put in a position of absolute power over others.

But this is misleading. The original intention of the study was to show how prisoners behave under duress. To aid that effort, the guards were briefed before the experiment began on how to behave (i.e. referring to the prisoners by number only and generally disrespecting them) and were reminded throughout the study to be “tough”.

The BBC partially replicated this sensational study in a made-for-television special but this time, the guards hadn’t been given any prior instructions. And the result must have greatly disappointed the show’s producers. No major drama, no dehumanization, no revelation of humanity’s evil. Instead, the prisoners and guards got along swimmingly.

Zimbardo’s botched experimental design leads me to agree with Bregman. The Stanford Prison Experiment is no proof of inherent human brutality.

Milgram’s Shock Experiments

In 1961, Yale University’s Dr. Stanley Milgram assigned study participants to a “teacher” role and informed them that a student sat in another room wired to an electrical shock machine. The teacher was to gradually increase the level of shocks applied to the student even as they heard cries of pain coming from the other room. Incredibly, 65% of the study participants completed the full treatment of shocks to the student.

Coming on the heels of WWII and the Holocaust, the study supposedly demonstrated the lengths people would go to bow to authority. This study has been replicated with similar results (unlike the Stanford Prison Experiment).

Bregman tries to view the experiment’s results in a positive light. His hypothesis is that the study participants simply wanted to be helpful to the researchers. In social research, demand characteristics refer to the idea that subjects alter their behavior to demonstrate what they expect the experimenter wants to see. In Bregman’s eyes, these participants are innately good people because they wanted to aid the experimenter, not harm the student.

While Bregman’s idea may have some validity, I question what he considers “good” and “evil” in this case. If an action is “good” only because someone else wants us to do it, and we are therefore helping them, is that not a kind of moral relativism? I hope we can all agree that causing unprovoked harm to another person is an absolute wrong, and the mental gymnastics involved in calling this behavior “good” reeks of retroactive justification.

While I normally try not to paint the world in black and white, Bregman’s central thesis forces us to consider where we draw the line between good and evil. Bregman never bothers to define what he considers to be “good” but I’ll offer my own definition: choosing the path that minimizes total harm inflicted. When we apply this definition to Milgram’s study, we see that the total harm to the student outweighs the total harm (inconvenience, really) done to the experimenter by refusing to continue with the study. Therefore, any rational person attempting to do “good” should bow out of the experiment, and I cannot subscribe to Bregman’s argument that this study proves humanity’s inherent good through “helpfulness”.

Nazism

Bregman then tries to downplay Nazism. The trial of Holocaust organizer Adolf Eichmann inspired philosopher Hannah Arendt’s idea of the “banality of evil”, which maintains that Eichmann was motivated by not fanaticism but by complacency.

Bregman devoted an early chapter to explaining how Homo sapiens evolved to rule the earth through superior sociability and learning skills. It is precisely this tendency to “go with the flow” and adopt the mentality of others that makes us human. But that doesn’t mean we should excuse complacency in the face of evil. Applying our definition above of “good” shows that total harm inflicted by complacency is much greater than that caused by standing up for what is right.

Bregman tries to reframe humanity’s sheeplike tendencies as either proof of intrinsic good or as neutral behavior that cannot be used as evidence of our innate evil. Yet I remain convinced that inaction in the face of evil is an evil itself.

Recognizing our humanity

This is not to say that Bregman’s arguments are worthless. I agree that active evil, evil independently conceived, is probably rare in our society. And that most people want to do good, although their definition of good may differ from my own.

Bregman also makes a compelling case against the idea that humans are innately bloodthirsty and war-mongering. He cited several examples from historical battles where soldiers aimed over each other’s heads or filled muskets several times over just to avoid having to shoot. Only 15% of American soldiers in WWII ever fired a weapon in action, even when ordered to do so.

That percentage no longer holds true in today’s military. Infantry training now involves a desensitization process where soldiers lose their reluctance to shoot at another human. Though the need for them to shoot at all is becoming less likely with the arrival of armed drones. The more distance we can put between ourselves and those we wish to harm, the more willing we are to commit acts of violence.

People find killing another human cognitively difficult when they recognize them as another human being. A classic example comes from George Orwell who fought in the Spanish Civil War:

“A man presumably carrying a message to an officer, jumped out of the trench and ran along the top of the parapet in full view. He was half-dressed and was holding up his trousers with both hands as he ran. I refrained from shooting at him…I did not shoot partly because of that detail about the trousers. I had come here to shoot at ‘Fascists’; but a man who is holding up his trousers isn’t a ‘Fascist’, he is visibly a fellow-creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t feel like shooting at him.”

Bregman maintains that recognizing the humanity in each other is one of the most direct ways to combat the rising tide of distrust in society. He cites Norwegian prisons as a shining example of this idea in action.

Instead of the punitive approach favored by the American prison system, Norwegian prisons are designed to be rehabilitative. Many Americans might mistake one of these prisons for a resort complete with yoga classes, cross-country ski trails, and woodworking shops (fully equipped with potentially lethal tools). Guards are encouraged to form relationships with prisoners and to always treat them as fellow human beings.

The results are startling. Norway’s recidivism rate is only 20%. Compare that figure to the U.S. where 76% of criminals are repeat offenders and you can see that these relatively cushy prisons pay for themselves.

Recognizing the humanity in others requires us to bridge the divide between groups. Too often our innate tribalism causes us to objectify members of out-groups and view them with suspicion. We see this perspective in action when tracking support for Trump’s proposed wall along the border with Mexico. Americans who live closer to the border are less likely to approve of a wall against our neighbors.

Our innate xenophobia is a classic case of System 1 thinking, a decision-making process that is instinctual and low-effort. Thinking is hard work! We can’t deeply analyze every decision in our everyday lives so we default to System 1 thinking unless the situation calls for more brainpower (like calculating the tip on a restaurant bill). Anything requiring concentration will kickstart System 2 thinking.

Deciding whether or not to trust someone is a cognitive burden. To compensate, we fall back on heuristics like in-groups and out-groups to shortcut those decisions. We must make an effort to overcome this tendency, trigger our System 2 thinking, and actively evaluate strangers as fully-dimensional human beings, instead of relying on shallow stereotypes or an us-vs-them mentality.

Rules to live by

Bregman ends his book with ten “rules to live by”. While many of these rules seemed rather obvious (“Think in win-win scenarios”), a few were worth incorporating into daily life.

When in doubt, assume the best

Deciding to not trust another person results in asymmetrical feedback: if I trust someone to watch my laptop while I take a bathroom break, I’ll receive either a confirmation of that trust if my laptop is still there upon my return or a contradiction if I return to find both the stranger and my laptop missing. But if I didn’t take a chance on trusting that person, I’d never know if I was right. I could never update my opinions and way of thinking.

Temper your empathy, train your compassion

Empathy is exhausting. Our sympathetic reaction to negative news is why we feel so drained and pessimistic after a daily barrage of bad press.

Instead, Bregman suggests we should feel for others and send out warm feelings of care and concern. He classifies this attitude as “compassion”—a more active attitude that leaves us feeling energized instead of drained.

Love your own as others love theirs

Recognize the humanity in everyone. Extend your circle of love and compassion outside your family and friends, and remember that every stranger you meet is someone’s son, daughter, mother, father, husband, or wife.

This mentality is more cognitively demanding and will require System 2 thinking. But with practice, we can train our brain and form a habit of embracing the full spectrum of a person’s humanity.

Don’t be ashamed to do good

Every spring, I trek out to my neighborhood park to pick up the litter revealed by the melting snow. And every year, I feel self-conscious wandering around the park, garbage bag in tow, grabbing at old chip bags with my trash picker.

I don’t perform this annual rite of spring cleaning to spur anyone else into action. On the contrary, I’d much prefer if there were no witnesses at all. But Bregman reminds me that doing good can be contagious and that my act of service can have ripple effects beyond the park.

After all, how can we expect to live in a culture of selflessness if we aren’t leading by example?

What’s next

While I found some of Bregman’s arguments flawed, his book still reframed my view of human nature and convinced me that suspicion and cynicism are not default human behaviors. Intervention is still possible to rebuild trust by buying into a belief of goodwill and positivity.

Beliefs are the fabric of society, the only threads tying us together. We must remember that hope is a type of belief. It is only through collective hope that anything of value has been achieved in society. Dismayed we are divided. Hopeful we are united. We must all believe in a positive future to make it so.

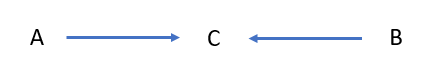

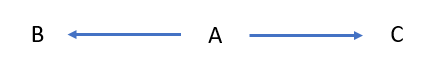

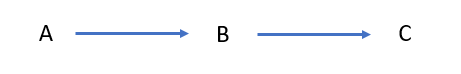

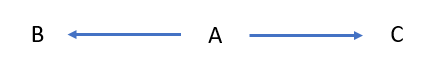

![]() , where the

, where the ![]() operator implies an action. In other words, if there is a difference between the probability of an outcome

operator implies an action. In other words, if there is a difference between the probability of an outcome ![]() given

given ![]() and the probability of

and the probability of ![]() given

given ![]() in a perfect world in which we were able to change

in a perfect world in which we were able to change ![]() and only

and only ![]() , then confounding is afoot.

, then confounding is afoot.